There is a very famous play by the British playwright Samuel Beckett called Waiting for Godot. In it, two characters spend their time sitting at the side of a road, waiting for someone called Godot to arrive. From the beginning of Act 1 to the end of Act 3, they sit there, idly and vainly, going round and round in circles in the same absurd conversation. At the end, they are left waiting as futilely as at the beginning. They have no idea who Godot is. They sometimes wonder whether they are really waiting for anyone at all. Yet there is nothing else for them to do but to sit around and wait in utter futility.

Life for an unbeliever is something very like this. Some years ago, my attention was drawn to the description, by a contemporary painter, of the message of his art: “My work attempts to express the sense of loneliness, of alienation and utter frustration felt by modern man, as he struggles to extract some kind of meaning from his apparently senseless existence.” Does this not sound just like the senselessness of the two characters in Waiting for Godot? Even the name of the person for whom they are waiting, Godot, sounds like a diminutive form of God.

There is an emptiness, an aching void, at the center of godless modern man. He is aware of this emptiness, and will go to any lengths to avoid it, or to fill it. Some find an escape in the oblivion of drugs or the brain-bashing rhythms of modern music in whichever form is current. Some seek to impose meaning on their lives through the strait-jacket of political ideology. Others seek an answer in exotic religious sects and offbeat mysticism, anything from astrology to witchcraft to worship of Gaia the earth-mother, the latest in a whole series of modern back-to-nature godlets. But the emptiness nevertheless persists. Godless modern man is waiting for something, but he knows not what. And he sees no hope, no meaning, because he does not know for whom or for what he is waiting. It is an empty waiting, dark with ignorance, bereft of hope, bleak with despair. Godless modern man is still waiting for Godot, and Godot, like tomorrow, never comes.

How different is the waiting of the Christian! The Christian inhabits the same world as godless modern man. He sees the same sorrows, the same suffering. He experiences the same evils, must watch his work corrupted and come to nothing in the same way. He knows, as surely as godless modern man, that there is something desperately wrong with this world of ours, something that urgently needs to be set right. He longs for the world to be changed, to be set right. All the ugliness, the loneliness, which besets godless modern man with such emptiness and despair, is known as surely to him. And yet, in the face of it all, the Christian is not beset with despair, but filled with an unquenchable hope. Ahead he sees not impenetrable darkness, but inextinguishable light. And the reason for this completely different response is simply explained; for the Christian is not waiting for Godot; he is waiting for God!

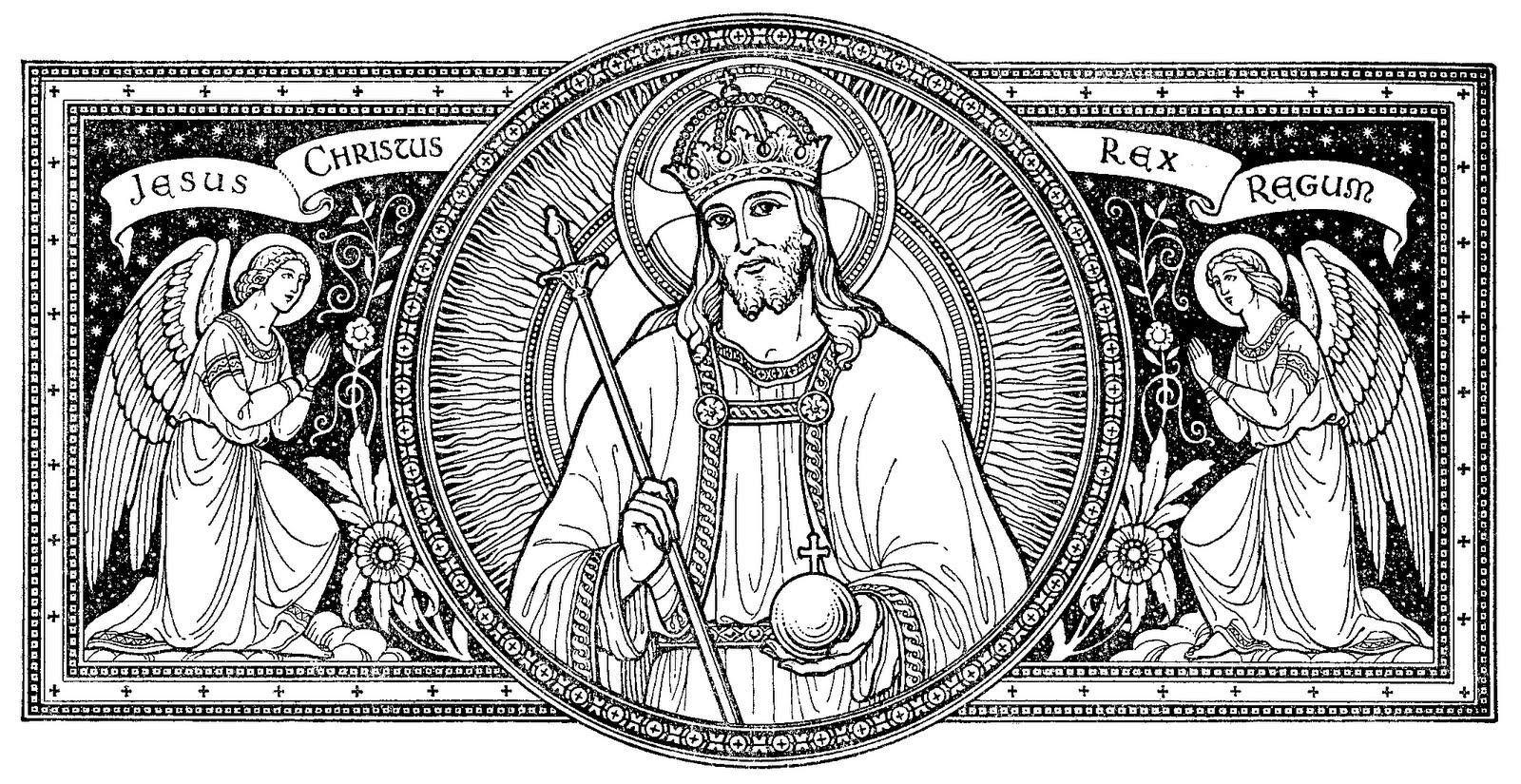

A Christian is not waiting for some vague manifestation of God; the Christian is waiting for God made Man amongst us. When the Christian waits for God, he waits for the Son of God, the Lord Jesus Christ, the Word made Flesh who lived among us In the midst of sorrow, suffering, tragedy, even apparent meaninglessness in the world, the Christian has glimpsed the glory of the Lord, something of the inconceivable end he has in store for his creation. All the dark and ugly things we experience are things which the power of God overcomes, which he can even use for our good. And all of them ultimately make sense because we are waiting for a God who really is coming, a God whom we can and do know face to face. The God for whom we wait is a person, and he has come to save us.

So it is that the Christian waits with unquenchable hope for a God who comes. The darkness of this world is for us merely a shadow which will be banished forever when God sheds his glorious light upon us. It is significant that the last book of the Bible, the Book of Revelation, is a book which practically explodes with a message of hope in the midst of disaster. And the climax of that book, in its final verse, is the cry "Come, Lord Jesus!" Let this be our hope, our message for this Advent. Let us not be a hopeless people, waiting in despair for a Godot who never comes. Rather, let us be a people brimming with hope and joy, our eyes fixed on the glorious future He has already prepared for us; let us be a people waiting - for God. Amen.

Fr Phillip

.jpg)